Bottom-up creation of data-driven capabilities: weak supporters *10 = strong support

My previous post addressed the scenario of executives or managers saying they want data-driven capabilities but not accepting data-driven analyses when the findings are presented to them. As I discussed in that post, I think the best first step in such a situation is to regroup and streamline your workflow, automating as much of your more repetitive tasks as possible, in order to free up your time so you can devote more attention to bringing those managers on board. This post focuses on one of many possible next steps: building up support in a wide variety of seemingly trivial areas of your organization.

When I start working with any organization, my first impulse is too look at the flagship products and programs – those things that bring in the most revenue, require the most resources, eat up most people’s time, and get the most attention in press releases and board meetings. It’s easy to find inefficiencies and other problems in most flagship programs, partially because any program or product is created and maintained by humans, which means it will always have room for improvement. But beyond the whole nothing’s-perfect aspect of the issue, I think flagship programs often have many obvious problems because they are some of the oldest programs an organization has. That means they’ve had a lot of time collect organizational debris, retaining practices and policies whose functions made sense 20 years ago but don’t make much sense now, and the people who work those programs have had a long time to develop ad-hoc workarounds to deal with and get used to the inefficiencies, which perversely makes it inefficient, on a personal level, to change things that are inefficient on an organizational level.

All of these conditions create an environment in which suggested changes to flagship programs get met with anything from reticence to skepticism to incredulity. These are, after all, programs that are doing well in the sense that they are bringing in more customers, revenue, attention, etc. than their smaller counterparts, and even if their size is the main reason they are bringing in more of their good things than the other programs, managers get a little panicky at the hypothetical possibility that a change could in some way make the flagship program bring in less of those things than it is right now. For most managers I’ve talked to, change equals risk equals cost equals stop talking to me.

I’ve tried to make the case that changes to big, protected programs make sense. I’ve brought in loads of research literature that shows that current practices are inefficient or that alternative practices have a good chance of being more efficient. I’ve collected input from personnel actually involved in the day-to-day workings of the programs who complain about outdated practices or features, or who suggest simple changes that could make their jobs a lot easier. None of that stuff works.

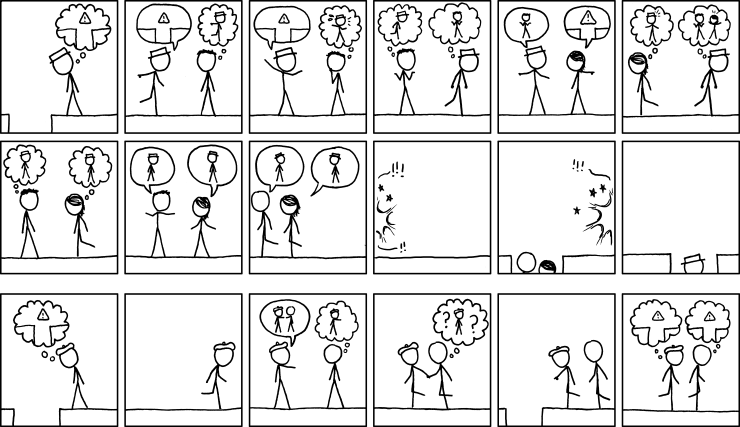

Information by itself doesn’t often lead to action because people can always question that information’s completeness, relevance, or urgency. I can’t count how many times I’ve had analysis countered with “well, that might be true of those cases, but my situation works differently.” Showing convinces people, telling doesn’t. I’ll address the issue of how to do show-not-tell at the analytic level in a future post. An alternative is to do it at the organizational level by forming a coalition of lots of weak players.

Instead of focusing on a flagship program, find a program that most people don’t see as very important. You want to find people who have a lot of gain and very little to lose from being entrepreneurial. (Sometimes you can find people who are just innately entrepreneurial who happen to occupy powerful positions within the organization. In those cases, you’re probably don’t need to figure out how to build data-driven capabilities from the bottom up because those people are likely to help you introduce those capabilities from the top down. ) You probably don’t want to look at completely new programs, as people who manage those programs are probably just worried about surviving. The ideal candidates, in my experience, are people whose programs have already proven their value, but have proven to have quite small value compared to the value of the flagship programs.

Those people almost always feel that their program doesn’t get the attention it deserves. They’re usually right. They have a stable position in the organization but have enough ambition to be able to stomach some risk. Find those people. Find out what they’re doing and how they do it. Come up with proposals to make what they do more data-driven and pitch those proposals to them. Some will accept and others won’t. Work with the people who will work with you. Once you’ve streamlined their decision making and given them insights into their products that no one else in the company has, go back to the people who first turned you down and pitch those results to them. That should get you some more supporters.

The beautiful thing about bottom-up coalition building, especially in organizations that only have only double- or trip-digit numbers of employees, is that you don’t have to do anything with the coalition once you’ve built it. In relatively small organizations, people talk to one another. Managers talk to general managers who talk to VPs. Instead of getting one powerful player saying nice things about data-driven decision making, get ten weak players saying those nice things. The effects, in my experience, tend to be largely the same.

Once you have multiple examples of data-driven activities working for different sections of your organization, it’s much easier to convince those flagship folks that they ought to give it a try too: instead of telling them what they can do to improve, you can show them how other parts of the organization have improved from doing the things you’re advocating.

If you want to comment on this post, write it up somewhere public and let us know - we'll join in. If you have a question, please email the author at schaun.wheeler@gmail.com.