A numerical heuristic is still just a heuristic

The marketing and business research literature has kind of impressed me. I’m used to conflict research. Marketing research seems to be just a prone to unfounded assumptions and unwarranted conclusions as the studies of Afghan insurgencies or Mexican counter-narcotics operations – the low points of each kind of research seem to be about the same. It’s the high points that are different. I’ve seen a lot of three-anecdotes-equal-a-trend and trust-me-I’m-an-expert arguments in the marketing research, but I’ve also seen a whole lot of really rigorous methods and, in many cases, a refreshing attention to research design.

Given that I’ve just come from an analytic environment where, to my great frustration, the line between anecdote and evidence was routinely ignored, I’ve been surprised that I’m actually feeling quite ambivalent about some attempts to standardize insights for the sake of decision-making. I spent the last three years trying to get people to explicitly lay out their heuristics – to base their assessments on some method instead of a gut feeling – but now I’m seeing papers that advocate very explicit heuristics and let me tell you: explicit for it’s own sake isn’t necessarily better.

Take the “Net Promoter Score” (NPS) for example. I won’t go into the details here (see Wikipedia and Google Scholar). Long story short: it was thought up by a high-up at Bain, first published in the Harvard Business Review, and is used to assess performance and customer satisfaction at all sorts of successful companies – GE, for instance. You ask people questions like “How likely would you be to recommend [a hotel, restaurant, service, company, etc.] to a friend?” and have them answer on a scale running from 1 to 10. You take the percentage of 9s and 10s, subtract the percentage of 1s through 6s, and ignore the 7s and 8s to get a score ranging from -1 to 1. Traditionally, you multiply that by 100…I’m not sure why. The NPS is supposed to tell you how many “promoters” you have – people who will advocate for your product or service by telling others to use it – relative to the number of detractors.

The NPS has been criticized on the grounds that it ignores a lot of information, isn’t grounded in any theory of probability, and it seems to track pretty closely with traditional customer satisfaction measures. From the moment I saw NPS, I’ve wanted to hate it for all those reasons. It’s just taking a scale and weighting some parts differently than others with no regard for the probability of any particular score appearing among a given sample.

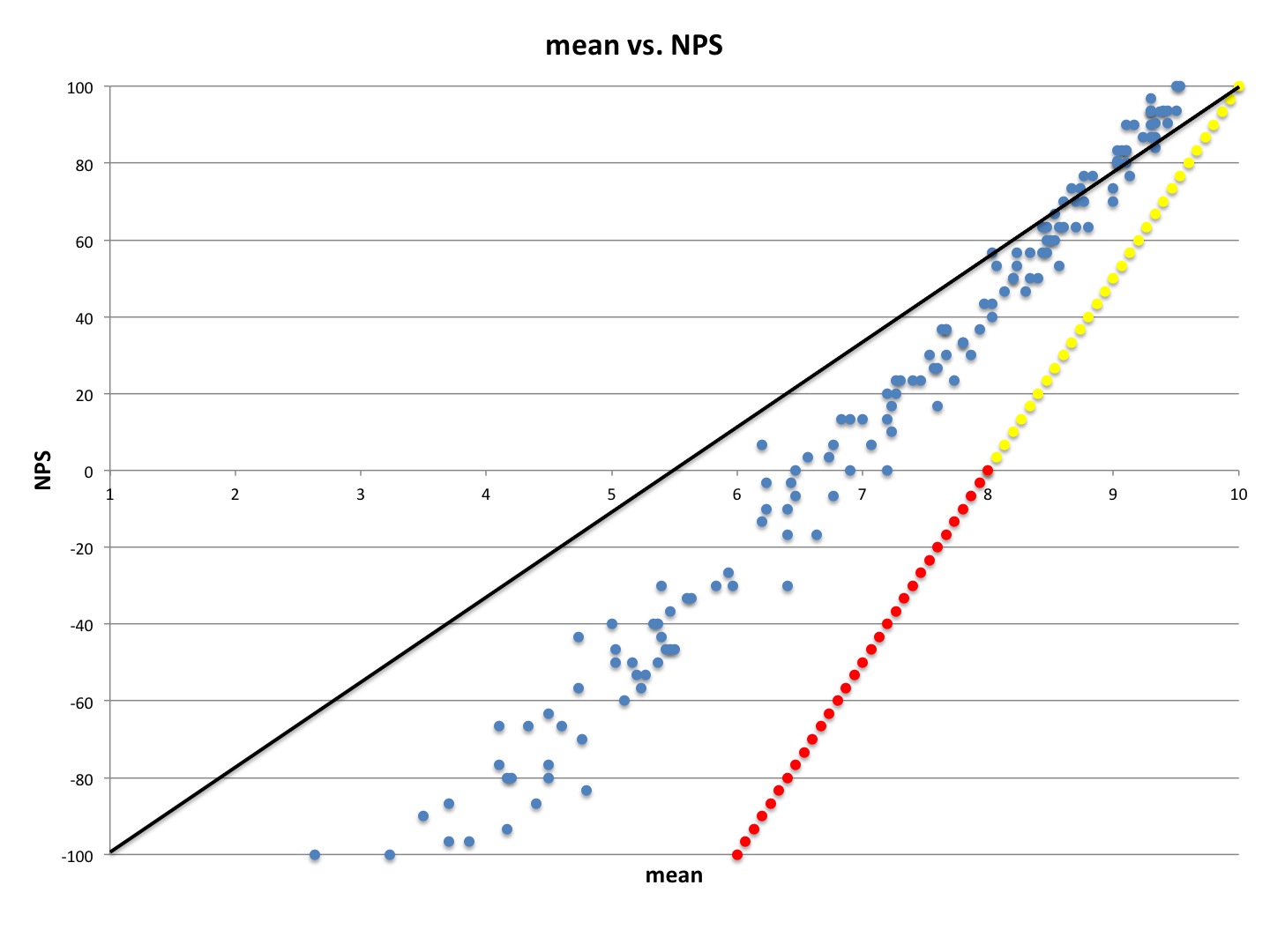

But over the last week, I’ve started to see how it could be useful. Take a look at the graph below. I simulated the full range of possible NPS scores and introduced some random variation to compare the NPS with the range of values that we could expect to see if we instead calculated a plain-old average. The blue points are based on 150 simulations of responses to 30 different questions. Ignore the yellow and red points for a second – I’ll come back to those.

The black diagonal line is where the blue dots would be if NPS and the mean matched up exactly. The very highest NPS scores portray the data in a more positive light than the mean would. NPS of about 75 and down pretty consistently portrays the data in a more negative light than the mean would. In other words, NPS does exactly what is says it does – it really values very high responses, treats ambivalent responses as equivalent to low responses, and ignores just-higher-than-middle responses. As you can see from the horizontal spread of the blue markers, there are fewer ways for a high score to be high than there are for a low score to be low – only 2 values of the 10-point scale are “promoters” while 6 out of 10 are “detractors.” And we’re not really loosing too much information if we use NPS – this simulation showed a .99 correlation between the NPS and the mean.

The NPS is a heuristic, not a statistic. It suggests areas that need improvement by highlighting weaknesses and downplaying strengths. The purpose is to facilitate decision making, not to contribute to a deeper understanding of a subject. In general, I’d probably rather people used NPS to assess a situation if the alternative is to just look at a handful of probably cherry-picked quotes or second-hand observations.

But heuristics have pitfalls if they’re not used carefully. I created additional values for the borderlines of the heuristic’s categories. The yellow dots represent what happens when someone decides to answer a question just below the “promoter” cutoff. The top yellow dot represents a case of all 30 questions being answered with a 10. The descending dots represent 29 tens and one eight, 28 tens and two eights, and so on until all 30 questions are answered with an eight. The red represent what happens when someone decides to answer a question just below the “neutral” cutoff – they start with all eights, and one by one include more sixes until they are all sixes. Starting with all tens and incorporating sixes until they are all sixes follows the same path as the yellow and red lines combined.

Because NPS sets a much lower bar for failure than it does for success, it’s possible to have a really high average but have an NPS in the toilet. So while NPS tends to just be a somewhat less-forgiving version of an average, it can in some cases drastically distort the record of a product, service, or employee based only relatively minor differences in what part of the 10-point scale people marked. That means we ought to be really, really sure that when people mark a point on the scale, that they really mean to mark that point. That’s what concerns me. The standard is to use a 10-point scale of how likely a person feels he or she would be to recommend something. The scale and the question both have problems that make NPS a pretty bad heuristic.

Regarding the scale: I remember sitting in a seminar in graduate school where we discussed scale development. The seminar leader, who had developed and used many, many scales over the course of his career, said something like, “People have done all sorts of studies on scales. They’ve studied what happens when you use an even-numbered scale instead of an odd-numbered scale. They’ve studied what happens when you use scales of different sizes. They’ve studied what happens when you randomize the order of the questions. All those studies have produced really just one basic finding, and that’s that people are going to answer the questions however the hell they want.” Technically, that’s not entirely true – there are some other consistent findings about scale usage – but it’s mostly true.

If and NPS question asked something like “how many times have you recommend X?” then the scale might make a little more sense: people might lie or not remember the correct answer, but at least we could be sure that they understood the difference between, say, a 7 and an 8 on the scale. But what’s the difference between being seven likely to recommend and eight likely to recommend? The numbers have no meaningful interpretation. We want to know the difference between “would recommend,” wouldn’t recommend”, “don’t know,” so that’s what we ought to ask. If we want gradations, we should at least use a scale where the “don’t know” option could be a middle point at zero with the scale running up to +5 and down to -5 from that point. (See here, for example). We still wouldn’t have a meaningful interpretation for the numbers, but at least we’d have a better basis for grouping promoters and detractors. With the traditional 10 point scale, there’s just no basis for that differentiation.

Regarding the question: people aren’t good at assessing intention – especially their own. And just because we ask a question doesn’t mean people give us the answer to that question. We’re saying, “tell us your intended course of action” and people are answering with “I feel good.” Using a better scale might mitigate this problem a little bit. As things stand now, how do you answer a question about likelihood on a 10-point scale? You can’t even treat the numbers as percentages – 20% likely, 60% likely, etc. – because there’s no zero. It probably wouldn’t be a bad idea to rephrase the question as well – something like “If someone you knew told you they wanted to buy X, would you tell them to do it?” People often are better at answering questions when the question is phrased as a scenario rather than an abstract “likelihood.”

Using a problematic heuristic might be more useful than harmful in situations where you need to make a discrete decision and where the consequences of making the wrong decision aren’t that bad. For example, if you normally send your customers to one hotel, and NPS suggests that their experiences weren’t that good, you can drop that hotel because you have many others to choose from, and because that hotel probably won’t hold it against you if you decide later to come back to it. You decision isn’t going to put the hotel out of business, isn’t going to leave you with no place to put your customers, and isn’t going to burn any bridges. But what about assessing an employee’s performance with NPS? You’ve probably invested in that employee, and bringing on someone new could be difficult. If you cut a bonus or terminate employment based on a bad NPS, you’ll be severing a relationship that possible wasn’t all that bad – the NPS could have been low but the mean could have been quite high.

So NPS makes more sense in tactical decisions – in deciding specific actions, not long-term trajectories. Actual statistical measures like the mean would be better for strategic decisions, where the cost of making the wrong decision is higher. Even tactical decisions, it wouldn’t hurt to compare NPS for the same person across years/months/business cycles/customer interactions and look at the big picture to minimize individual distortions of a person’s record.

Heuristics are necessary, and I generally prefer a systematic heuristics to an unsystematic one. But once those numbers are out there it’s all to easy to pretend they are measuring something real like performance. They don’t do that. Heuristics like NPS are just convenient summaries of rules-of-thumb. NPS accentuates the bad to help people make short-term, low-consequence decisions. That’s useful. But long term, more consequential decisions deserve better measurement.

If you want to comment on this post, write it up somewhere public and let us know - we'll join in. If you have a question, please email the author at schaun.wheeler@gmail.com.